Направленная доставка противовоспалительных агентов в зону ишемически-реперфузионного повреждения миокарда с помощью наноразмерных частиц

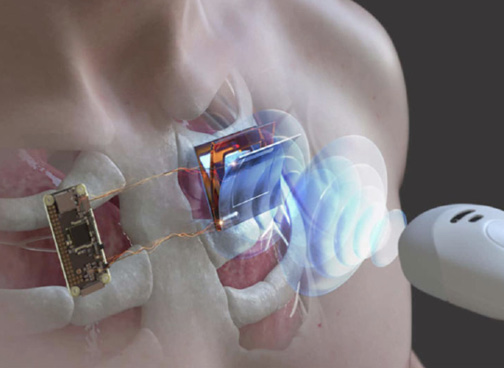

Атеросклероз представляет собой типичное возраст-зависимое заболевание, поэтому увеличение средней ожидаемой продолжительности жизни в большинстве стран мира в последние несколько десятилетий сопровождается параллельным увеличением смертности от инфаркта миокарда (ИМ) и сердечной недостаточности ишемического генеза [1][2]. Прогнозы экспертов свидетельствуют от том, что эта тенденция сохранится до 2050г [3]. Ранняя реваскуляризация миокарда при ИМ сопровождается значимым улучшением прогноза, однако восстановление кровотока по инфаркт-зависимой артерии приводит к формированию реперфузионного повреждения миокарда. В определенных ситуациях реперфузионное повреждение может иметь необратимый характер и приводить к увеличению размера инфаркта в 2 раза относительно объема, имевшего место в момент прекращения ишемии [4]. Механизмы раннего ишемически-реперфузионного повреждения (ИРП) миокарда включают такие аспекты, как оксидативный стресс, гиперконтрактура кардиомиоцитов, кальциевая перегрузка и открытие митохондриальной поры [5]. При этом формирование очага некроза миокарда в результате ИРП всегда вызывает асептическое воспаление, направленное на удаление необратимо поврежденных клеток миокарда, а в дальнейшем и на репарацию повреждения, которая в силу ограниченного регенеративного потенциала сердца млекопитающих является неполноценной и сопровождается формированием постинфарктного рубца. Воспалительный ответ чрезмерной интенсивности и/или продолжительности может сопровождаться развитием дополнительного, вторичного повреждения миокарда, которое целесообразно рассматривать в контексте позднего реперфузионного повреждения [6]. Воспаление развивается и в отсутствие реперфузии; при этом восстановление кровотока усиливает воспалительный ответ и ускоряет его течение [7]. Последствиями такого повреждения являются диффузная гибель кардиомиоцитов, нарушение формирования рубца, эксцентрическое ремоделирование миокарда и увеличение риска развития сердечной недостаточности [8]. В связи с этим в последние 10 лет отмечается значительный интерес к применению небольших доз селективных противовоспалительных препаратов для лечения пациентов с ишемической болезнью сердца и профилактики сердечно-сосудистых осложнений [9]. Применение модуляторов воспаления и иммуносупрессантов в этом случае обусловлено возможностью воздействия не только на воспалительный ответ в миокарде, но и в атеросклеротической бляшке, что способствует ее стабилизации. Так, в исследовании CANTOS было показано, что назначение канакинумаба (антитела против интерлейкина (ИЛ)-1β) у пациентов с ишемической болезнью сердца и ИМ в анамнезе приводит к снижению первичной конечной точки на 17% [10], но сопровождается значимым увеличением частоты развития инфекционных осложнений, в т.ч. фатальных. Применение колхицина, нарушающего динамику сборки микротрубочек, через 1 мес. после ИМ, приводило к уменьшению первичной конечной точки на 23%, хотя при этом отмечалось значимое увеличение частоты развития пневмонии и диареи [11]. Эти результаты показывают наличие значимых побочных эффектов противовоспалительных агентов, связанных с их системным иммуносупрессивным воздействием. Одним из путей решения имеющейся проблемы является адресная или таргетная доставка молекул, подавляющих отдельные механизмы воспаления, в зону ИРП миокарда. Таргетная доставка предполагает связывание действующего вещества с наноразмерным носителем, что позволяет реализовать эффект пассивного таргетирования, основанный на феномене повышенной проницаемости и задержки [12]. Дополнительное уменьшение объема распределения лекарственного средства может быть достигнуто путем связывания нагруженных препаратом наночастиц с направляющими лигандами, т.е. молекулами, специфически взаимодействующими с поверхностными маркерами на клетках ткани-мишени. «Удержание» наноразмерных частиц в органе-мишени в этом случае способствует локальному высвобождению препарата и повышению его концентрации. В научной литературе последних лет появляются первые публикации, посвященные экспериментальной апробации способов таргетной доставки соединений с противовоспалительной активностью в миокард на моделях ИРП у лабораторных животных [13].

Целью обзора являются систематизация и анализ имеющихся публикаций, связанных с разработкой и экспериментальной валидацией способов направленной доставки противовоспалительных агентов в миокард при ИРП.

Новизна исследования: идентификация основных групп молекулярных мишеней для таргетного терапевтического воздействия с целью подавления асептического воспаления при ИРП миокарда, систематический анализ результатов исследований, посвященных таргетной доставке противовоспалительных агентов в зону инфаркта.

Методология исследования

Обзор проведен в соответствии с рекомендациями PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) для обеспечения точности и прозрачности процесса отбора, оценки и синтеза данных [14]. Исследование направлено на всесторонний анализ исследований направленной доставки противовоспалительных агентов в миокард при ИРП.

Критерии включения

- По типу исследований — экспериментальные исследования, описывающие результаты применения связанных с наночастицами противовоспалительных молекул при перманентной ишемии и ишемии-реперфузии миокарда.

- В зависимости от популяции — исследования на лабораторных животных, используемые для моделирования повреждения миокарда и оценки эффективности противовоспалительных вмешательств.

- В зависимости от методов и процедур — исследования, описывающие эффективность применения связанных с наночастицами препаратов на моделях in vivo.

- По типу исходов — качественные и количественные данные, описывающие эффективность адресной доставки с помощью наночастиц.

Критерии исключения

- Обзоры, комментарии, тезисы конференций и публикации без полного текста.

- Работы на языках, отличных от английского и русского (если не удалось получить перевод).

- Исследования, посвященные изучению содержащих наночастицы стволовых клеток, различных вариантов внеклеточных везикул с секретируемыми стволовыми клетками веществами, а также гидрогелей и микрочастиц с включёнными противовоспалительными агентами.

- Исследования, в которых оценивалась эффективность применения связанных с наночастицами противовоспалительных агентов на моделях изопротеренол-индуцированного ИМ, а также на моделях антрациклиновой кардиотоксичности.

Источники данных и стратегия поиска

Поиск литературы был проведен в следующих базах данных: PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar и Web of Science. Стратегия поиска включала комбинации следующих ключевых слов: «anti-inflammatory agent», «nanoparticle», «myocardial infarction», «ischemia», «reperfusion», «targeted delivery». В анализ была включена литература, опубликованная до августа 2025г.

В целях повышения полноты поиска использовался метод перекрестного поиска по ссылкам (backward and forward citation tracking) для включения дополнительных исследований, представляющих значительный интерес.

Процедура отбора исследований

Процедура отбора исследований соответствовала протоколу PRISMA. Первоначально проведен отбор по заголовкам и аннотациям, после чего полный текст был проанализирован для окончательного включения. Каждое исследование оценивалось двумя независимыми рецензентами на соответствие критериям включения и исключения, с последующим разрешением разногласий путем консенсуса или консультации с третьим экспертом.

Результаты

Таргетная доставка противовоспалительных препаратов при ИРП миокарда

Основные патогенетические молекулярные мишени, подлежащие управляемому подавлению при гиперэргическом воспалении, представлены рецепторами врожденного иммунитета и их сигнальными путями, белками комплемента, транскрипционным фактором κB, провоспалительными цитокинами и хемокинами (и их рецепторами), адгезионными молекулами, факторами активации и дифференцировки лейкоцитов, а также матриксными металлопротеиназами. Дополнительный позитивный эффект потенциально может быть достигнут за счет стимуляции механизмов, подавляющих воспаление, например, посредством экзогенного введения или усиления продукции противовоспалительных цитокинов или специализированных проразрешающих медиаторов [15]. Несмотря на достаточно большой выбор терапевтических мишеней, в настоящее время не существует одобренных для клинического применения при остром ИМ противовоспалительных препаратов. Это связано как с упомянутой ранее сложностью селективного воздействия на специфический механизм воспаления в нужном интервале времени, так и с недостатками фармакокинетики препаратов — недостаточной биодоступностью при системном введении, низкой стабильностью. Отдельной проблемой является наличие побочных эффектов ряда противовоспалительных лекарственных средств. Перспективным способом решения обозначенных трансляционных барьеров является таргетная доставка противовоспалительных средств в зону ИРП миокарда, которая может быть разделена на пассивную и активную.

Пассивная направленная доставка противовоспалительных молекул

Пассивная направленная доставка препаратов реализуется в том случае, когда связанные с действующим веществом наночастицы преимущественно выходят в измененные ткани через микрососуды с повышенной проницаемостью. Поскольку ИРП миокарда и других тканей характеризуется повреждением сосудов микроциркуляторного русла с нарушением контактов между соседними эндотелиоцитами и резким увеличением проницаемости [16], эффект пассивной доставки может быть применим к этим клиническим ситуациям. Последние 10 лет ознаменованы усилением интереса к проблеме направленной доставки противовоспалительных агентов в зону ИРП миокарда (табл. 1). В качестве наноразмерных платформ для иммобилизации препаратов используются разнообразные органические и неорганические наночастицы, диаметр которых составляет от 20 до 270 нм. Чаще используются органические наночастицы из липидов, полилактид-гликолида, фосфатидилхолина. Реже применяются неорганические материалы — золото и карбонат кальция [20, 29]. В одной работе были использованы наночастицы мезопористого полидофамина с термочувствительным покрытием из хитозана [30]. Для модуляции процесса воспаления применяются различные действующие вещества, связанные с обозначенными выше наночастицами. Некоторые препараты уже одобрены для клинического применения. К таким относятся ирбесартан (блокатор рецепторов ангиотензина II 1 типа, стимулирующий рецептор, активируемый пероксисомным пролифератором γ (PPARγ)) [22]; обладающий кардио-протективным и противовоспалительным эффектами питавастатин [18]; нестероидное противовоспалительное средство целекоксиб [19]; иммуносупрессанты с противовоспалительным эффектом метотрексат [23] и циклоспорин А [28]; агонист PPARγ пиоглитазон [25]; колхицин, нарушающий динамику сборки и разборки микротрубочек [29]. В работе Richart AL, et al. [27] в качестве действующего вещества использовался аполипопротеин АI, входящий в состав липопротеинов высокой плотности и уменьшающий экспрессию интегрина β2 на эндотелии, что способствует уменьшению выхода нейтрофилов в ткань. Wang T, et al. (2024) связали с наночастицами эпигаллокатехин галлат — катехин зеленого чая, обладающий антиоксидантными и противовоспалительными свойствами [30]. В двух исследованиях терапевтическое воздействие было связано с деградацией мРНК провоспалительных молекул — CCR2 и фактора некроза опухолей-α, с помощью малой интерферирующей РНК и дезоксирибозима, соответственно [17][20]. С использованием наночастиц из полилактид-гликолида Fujiwara M, et al. (2019) осуществили доставку ингибитора TLR4 TAK-242 [24], а Yajima S, et al. (2019) применили для подавления воспаления агонист IP рецепторов простациклина ONO-1301 [26]. В одной работе для предотвращения повреждения внеклеточного матрикса в результате воспаления был использован пептид, связывающий внеклеточный индуктор матриксных металлопротеиназ, который подавляет активность ММП-2 и ММП-9 [21]. В исследовании Ikeda G, et al. (2021) была предпринята попытка одновременного использования двух препаратов с противовоспалительным эффектом, каждый из которых был иммобилизирован на наночастицах полилактид-гликолида — циклоспорина А и питавастатина [28]. Необходимо отметить, что оба препарата демонстрируют не только противовоспалительную, но и кардиопротективную активность, т.к. циклоспорин является ингибитором митохондриальной поры, и питавастатин активирует киназы, предохраняющие от реперфузионного повреждения.

Абсолютное большинство работ в области направленной доставки противовоспалительных препаратов выполнено с использованием экспериментальных моделей ишемии миокарда на мелких лабораторных грызунах — мышах и крысах. Только в одном исследовании была проведена дополнительная валидация результатов, полученных на грызунах, на модели ИРП миокарда у свиней [25]. В 60% исследований на грызунах использована модель ишемии миокарда с последующей реперфузией, тогда как в 40% была индуцирована перманентная ишемия без реперфузии. Модель хирургической окклюзии левой коронарной артерии в условиях искусственной вентиляции легких остается наиболее широко применимой для решения подобных задач [31]. В исследованиях на модели ишемии-реперфузии миокарда препараты направленного действия, как правило, вводились внутривенно однократно в момент реперфузии либо за 5 мин до реперфузии. При постоянной перевязке коронарной артерии препараты в большинстве случаев вводили в периинфарктную зону вскоре после наступления ишемии, хотя в некоторых работах осуществляли повторное, еженедельное внутрибрюшинное введение в течение 6 нед. [23] или трехкратное внутривенное введение через 30 мин, 48 и 90 ч после коронарной окклюзии [29]. Основным критерием эффективности препаратов, связанных с наночастицами, являлось уменьшение размера инфаркта или, при более длительных сроках наблюдения, размера постинфарктного рубца в сравнении с эффектом свободного препарата в эквивалентной дозе и наночастиц. Для подтверждения инфаркт-лимитирующего действия препаратов в некоторых исследованиях оценивали уровень кардиоспецифичных тропонинов [26][27]. С учетом основной цели терапевтического воздействия эффективность направленной доставки была подтверждена с использованием таких критериев, как выраженность инфильтрации миокарда моноцитами, макрофагами и Т-клетками, а также уровень экспрессии провоспалительных цитокинов (фактор некроза опухолей-α, ИЛ-1, ИЛ-6, ИЛ-17А и др.) и хемокинов (МСР-1) в миокарде и, в некоторых случаях, их концентрация в крови. При более длительных сроках наблюдения важное значение для верификации эффективности направленной доставки имела оценка функционального состояния левого желудочка по данным трансторакальной эхокардиографии. В ряде исследований в роли морфологической конечной точки выступала интенсивность программируемой клеточной гибели (апоптоз, пироптоз), которая значительно уменьшалась после введения таргетированных противовоспалительных средств [18][20][23][28-30]. Немаловажным элементом дизайна исследований, посвященных направленной доставке препаратов in vivo, является подтверждение факта накопления нагруженных препаратом наночастиц или самого препарата в зоне ИРП миокарда. Верификация накопления наночастиц была выполнена в половине проанализированных исследований с помощью методик флуоресцентной органоскопии, конфокальной микроскопии и трансмиссионной электронной микроскопии. В некоторых работах было доказано селективное накопление препарата в зоне ИРП миокарда методом высокоэффективной жидкостной хроматографии — масс-спектрометрии, что является неопровержимым доказательством эффективности разработанной системы доставки [18][22][24]. В отдельных исследованиях проводился анализ новых или известных молекулярных сигнальных путей, ответственных за противовоспалительный эффект направленной терапии. Так, Nagaoka K, et al. (2015) показали, что противовоспалительный и кардиопротективный эффект питавастатина, связанного с полилактид-гликолидными наночастицами, зависит от сигнального пути фосфатидилинозитол-3ОН-киназа-протеинкиназа. Tokutome M, et al. (2019) [18] подтвердили, что эффект наносистемы с пиоглитазоном реализуется через PPARγ [25]. Ikeda G, et al. (2021) доказали, что противовоспалительный эффект доставки циклоспорина А и питавастатина реализуется с участием, соответственно, компонента митохондриальной поры циклофилина и хемокинового рецептора CCR2 [28].

Активная доставка противовоспалительных препаратов с использованием специфичных направляющих лигандов

Активная доставка также основана на применении препаратов, связанных с наноразмерными носителями. В связи с этим описанный выше принцип пассивной доставки в данном случае сохраняет свою значимость, но селективность накопления препарата в поврежденной ткани может быть дополнительно увеличена путем помещения на поверхность наноносителя направляющих лигандов либо чувствительных к физико-химическим параметрам локальной среды молекул. В таблице 2 представлены результаты исследований, посвященных активной направленной доставке противовоспалительных препаратов в миокард при ИРП. В качестве действующих веществ в данном случае использовались неспецифически действующие агенты — золото [33] и полидофамин [34], а также низкомолекулярный антагонист CCR2 [32], природное соединение матрин [35], липидный противовоспалительный медиатор резолвин D1 [38] и ингибитор фосфодиэстеразы 4 рофлумиласт [39]. В двух исследованиях применялась комбинация дексаметазона и малой интерферирующей РНК против рецепторов конечных продуктов гликирования [36] и сосудистой клеточной адгезионной молекулы-1 (VCAM-1) [37]. Большой интерес представляет арсенал направляющих лигандов, используемых до настоящего времени для активного таргетирования миокарда. Если в первой работе, посвященной этому вопросу, для этой цели использовались антитела против CCR2, то в дальнейшем большее распространение получили биоподобные подходы, связанные с покрытием наночастицы поверхностными мембранами собственных клеток организма, несущих соответствующие белковые и гликопротеиновые комплексы, взаимодействующие с рецепторами в зоне повреждения. Для этой цели были использованы содержащие рофлумиласт наночастицы полилактид-гликолида, покрытые мембранами нейтрофилов и эндотелиоцитов [39], наполненные резолвином D1 липосомы, содержащие фрагменты мембраны тромбоцитов с Р-селектином [38], а также полидофаминовые наночастицы, покрытые мембраной макрофагов, несущей α4/β1 интегрин [34]. В работе Tartuce LP, et al. (2020) в качестве направляющего лиганда для доставки наночастиц золота использован липофильный катионный агент 2-метокси-изобутил-изонитрил, широко применяемый для доставки радиофармпрепаратов в сердце при позитронно-эмиссионной томографии [33]. В качестве мишени для активной направленной доставки препаратов в зону ИМ могут быть использованы поверхностные молекулы не только кардиомиоцитов, но и эндотелиоцитов. Известно, что в ходе воспаления и ангиогенеза эндотелиоциты экспрессируют avb3 интегрин, специфически взаимодействующий с RGD пептидом, что позволило Hou M, et al. осуществить активную доставку дексаметазона и малой интерферирующей РНК против VCAM-1 в миокард на модели ишемии-реперфузии у крысы [37]. Для решения задачи редокс-управляемого высвобождения матрина из ковалентных органических каркасов Huang C, et al. использовали тетрафенилэтен [35]. В последние годы отмечается тенденция к разработке более сложных, многокомпонентных систем активной доставки, содержащих в своем составе наноразмерный носитель, несколько действующих веществ с разным механизмом действия, направляющий лиганд и редокс-чувствительную группировку. Примером такой многофункциональной платформы может служить система доставки дексаметазона и малой интерферирующей РНК против рецепторов конечных продуктов гликирования на основе наночастиц мезопористого кремнезема, снабженная направляющим лигандом в виде простагландина E2 и редокс-чувствительным элементом, содержащим поперечно сшитый теллуром полиэтиленимин [36]. Конструирование подобных систем, требующее междисциплинарного подхода, а также их последующее тщательное испытание на биологических объектах может способствовать решению сложной задачи — таргетной модуляции воспаления при ИМ.

Таблица 1

Исследования, посвященные пассивной направленной доставке противовоспалительных агентов в зону ИРП миокарда

|

Материал и диаметр НЧ |

Действующее вещество |

Вид животного, способ и режим введения НЧ |

Модель ИРП миокарда |

Результат (по сравнению с контролем) |

Источник |

|

Липидные наночастицы (70-80 нм) |

миРНК против CCR2 |

Мышь, однократно в/в одновременно с реперфузией |

Ишемия 35 мин + реперфузия 24 ч |

↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ инфильтрации моноцитами и макрофагами |

[17] |

|

Полилактид-гликолид (159 нм) |

Питавастатин |

Крыса, однократно в/в одновременно с реперфузией |

Ишемия 30 мин + реперфузия 24 ч или 4 нед. |

Накопление в зоне ИРП; ↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ инфильтрации моноцитами; ↓ экспрессии MCP-1; ↓ активации NFκB; ↓ апоптоза; ↓ фиброза; ↑ ФВ и ФУ ЛЖ; ↓ КДР и КСР ЛЖ; участие PI3K-Akt пути |

[18] |

|

Стабилизированная микроэмульсия (110 нм), помещенная в гидрогель из поливинилового спирта и полвинилпирролидона |

Целекоксиб |

Мышь, однократно интрамиокардиально сразу после начала ишемии |

Перманентная ишемия 30 сут. |

↓ ремоделирования ЛЖ; ↑ ангиогенеза; ↑ ФУ и ФВ ЛЖ; ↓ КДО и КСО ЛЖ |

[19] |

|

Наночастицы Au (80 нм) |

Дезоксирибозим против мРНК ФНО-α |

Крыса, однократно интрамиокардиально сразу после начала ишемии |

Перманентная ишемия 3 сут. |

Накопление в сердце; ↓ инфильтрации мононуклеарами; ↓ апоптоза; ↓ экспрессии ФНО-α, ИЛ-1, ИЛ-6 и NO-синтазы в миокарде; ↑ ФУ и ФВ ЛЖ; ↓ КСО и КДД ЛЖ |

[20] |

|

Парамагнитные Gd-содержащие флуоресцентные мицеллы (20 нм) |

Пептид, связывающий внеклеточный индуктор ММП |

Мышь, однократно в/в одновременно с реперфузией |

Ишемия 30 мин + реперфузия 24 ч |

Накопление в зоне ИРП; ↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ зоны гиперусиления на МРТ; ↓ ММП-2 и -9; ↑ ФВ ЛЖ |

[21] |

|

Полилактид-гликолид (200-220 нм) |

Ирбесартан |

Мышь, однократно в/в одновременно с реперфузией |

Ишемия 30 мин + реперфузия 3, 6, 12 ч, 1, 2 или 21 сут. |

Накопление в моноцитах и в зоне ИРП; ↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ инфильтрации моноцитами; ↓ экспрессии MCP-1; ↑ ФУ и ФВ ЛЖ; ↓ активации NFκB; ↑ PPARγ |

[22] |

|

Липидные наночастицы (60 нм) |

Метотрексат |

Крыса, 1 раз в нед. в/б в течение 6 нед. |

Перманентная ишемия 6 нед. |

↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ инфильтрации макрофагами и Т-клетками; ↓ апоптоза; ↓ АФК; ↑ СОД и КАТ; ↑ экспрессии VEGF и рецепторов аденозина; ↓ фиброза; ↑ ФВ ЛЖ; ↓ КСО и КДО ЛЖ; ↓ толщины МЖП |

[23] |

|

Полилактид-гликолид |

TAK-242 (ингибитор TLR4) |

Мышь, однократно в/в одновременно с реперфузией |

Ишемия 30 мин + реперфузия 24 ч, 1, 2 или 4 нед. |

Накопление в зоне ИРП; ↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ инфильтрации моноцитами и нейтрофилами; ↓ экспрессии ИЛ-6 и MCP-1; ↓ фиброза; ↓ КДР и КСР ЛЖ; ↑ ФВ и ФУ ЛЖ |

[24] |

|

Полилактид-гликолид (271 нм) |

Пиоглитазон |

Мышь, однократно в/в одновременно с реперфузией |

Ишемия 30 мин + реперфузия 4 нед. |

Накопление в зоне ИРП; ↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ активности катепсина В; ↓ провоспалительных моноцитов; ↓ экспрессии генов провоспалительных цитокинов; ↓ КДД и КСД ЛЖ; ↑ ФВ и ФУ ЛЖ; участие PPARγ |

[25] |

|

Мышь, 3 раза в/в через 6, 24 и 48 ч после ишемии |

Перманентная ишемия 4 нед. |

↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ инфильтрации мононуклеарами; ↓ фиброза; ↓ КДД и КСД ЛЖ; ↑ ФВ и ФУ ЛЖ; ↑ выживаемости |

|||

|

Свинья, однократно в/в за 5 мин до начала реперфузии |

Ишемия 60 мин + реперфузия 24 ч |

↓ размера инфаркта |

|||

|

Липидные наночастицы, покрытые ПЭГ (200 нм) |

ONO-1301 (агонист IP рецептора PGI2) |

Крыса, однократно в/в за 5 мин до начала реперфузии |

Ишемия 30 мин + реперфузия 24 ч |

Накопление в зоне ИРП; ↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ ТнI; ↑ экспрессии VEGF, ангиопоэтина-1; ↓ экспрессии ИЛ-1β, ИЛ-6, ФНО-α; ↑ кровотока; ↑ ангиогенеза; ↓ отека кардиомиоцитов |

[26] |

|

Наноразмерные комплексы фосфатидилхолина |

Аполипопротеин AI |

Мышь, однократно в/в в начале реперфузии |

Ишемия 30 мин + реперфузия 1, 3, 5 или 14 сут. |

Накопление в зоне ИРП; ↓ ТнI; ↓ лейкоцитов в крови; ↓ лейкоцитов в миокарде; ↓ хемокинов в миокарде; связывание с нейтрофилами и моноцитами |

[27] |

|

Полилактид-гликолид (175 нм с циклоспорином А и 159 нм с питавастатином) |

Циклоспорин А и питавастатин (на разных наночастицах, вводимых одномоментно) |

Мышь, однократно в/в одновременно с реперфузией |

Ишемия 30 мин + реперфузия 24 ч |

↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ воспаления; ↓ апоптоза; ↓ экспрессии ИЛ-1β; участие циклофилина D и CCR2 |

[28] |

|

Наночастицы карбоната кальция (243 нм) |

Колхицин |

Крыса, 3 раза в/в через 30 мин, 48 и 96 ч после окклюзии |

Перманентная ишемия 7 сут. |

↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ экспрессии цитокинов в миокарде; ↓ СРБ, ИЛ-1 и ФНО-α в крови; ↓ пироптоза; ↓ фиброза; модуляция макрофагов |

[29] |

|

Мезопористый полидофамин с термочувствительным хитозановым покрытием (207 нм) |

Эпигаллокатехин галлат |

Крыса, однократно интрамиокардиально сразу после начала ишемии |

Перманентная ишемия 3 или 28 сут. |

↓ АФК; ↓ апоптоза; ↑ ангиогенеза; ↓ экспрессии ИЛ-6, ФНО-α, ИЛ-17А; ↓ фиброза; ↓ КСР ЛЖ; ↑ ФВ и ФУ ЛЖ |

[30] |

Сокращения: АФК — активные формы кислорода, ИЛ — интерлейкин, ИРП — ишемически-реперфузионное повреждение, КАТ — каталаза, КДД — конечное диастолическое давление, КДО — конечный диастолический объем, КДР — конечный диастолический размер, КСД — конечное систолическое давление, КСО — конечный систолический объем, КСР — конечный систолический размер, ЛЖ — левый желудочек, МЖП — межжелудочковая перегородка, миРНК — малая интерферирующая РНК, ММП — матриксная металлопротеиназа, МРТ — магнитно-резонансная томография, НЧ — наночастица, ПЭГ — полиэтиленгликоль, СОД — супероксиддисмутаза, СРБ — С-реактивный белок, TнI — тропонин I, ФВ — фракция выброса, ФНО-α — фактор некроза опухолей-α, ФУ — фракция укорочения, Akt — протеинкиназа В, MCP-1 — моноцитарный хемоаттрактантный белок 1, NFκB — ядерный транскрипционный фактор κB, PGI2 — простациклин, PI3K — фосфатидилинозитол-3ОН-киназа, PPARγ — рецептор, активируемый пероксисомным пролифератором γ, TLR — толл-подобный рецептор, VEGF — сосудистый эндотелиальный фактор роста, VCAM-1 — сосудистая клеточная адгезионная молекула-1.

Таблица 2

Исследования, посвященные активной направленной доставке противовоспалительных агентов в зону ИРП миокарда. Активная доставка основана на покрытии наночастиц мембранами клеток, применении направляющих лигандов, а также включении в состав наноконструкции редокс-чувствительных элементов

|

Материал и диаметр наночастиц |

Действующее вещество |

Направляющий(е) лиганд(ы) и/или |

Вид животного, способ и режим введения наночастиц |

Модель ИРП миокарда |

Результат (по сравнению с контролем) |

Источник |

|

Липидные мицеллы, покрытые ПЭГ |

BMS ССR2 22 (низкомолекулярный антагонист CCR2) |

Антитела против CCR2 |

Мышь, два в/в введения через 48 и 72 ч после начала ишемии |

Перманентная ишемия 12 сут. |

↓ размера рубца; ↓ инфильтрации моноцитами |

[32] |

|

Наночастицы золота (18 нм) |

Золото |

2-метокси-изобутил-изонитрил |

Крыса, однократно интрамиокардиально одновременно с реперфузией |

Ишемия 30 мин + реперфузия 24 ч или 7 сут. |

Отсутствие токсичности; отсутствие влияния на фиброз; ↓ TGFβ и ИЛ-6 в миокарде; отсутствие влияния на ФУ ЛЖ; ↓ окисленного глутатиона |

[33] |

|

Полидофаминовые наночастицы (103 нм), покрытые мембраной макрофагов |

Полидофамин |

Интегрин α4/β1 |

Крыса, однократно в/в через 2 ч после реперфузии |

Ишемия 45 мин + реперфузия 24 ч или 30 сут. |

↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ КФК-МВ, ЛДГ; ↓ экспрессии ИЛ-1β; ↓ пироптоза; ↓ АФК; ↓ фиброза; ↑ ФВ ЛЖ; ↓ активации NLRP3 инфламмасомы |

[34] |

|

Ковалентный органический каркас (105 нм) |

Матрин |

Тетрафенилэтен |

Мышь, однократно в/в на 5 мин реперфузии |

Ишемия 30 мин + реперфузия 28 сут. |

Накопление в зоне ИРП; ↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ ТнI и NT-proBNP; ↓ АФК; ↓ апоптоза; ↓ фиброза; ↓ гипертрофии кардиомиоцитов; ↑ ФУ и ФВ ЛЖ |

[35] |

|

Мезопористый SiO2 (200 нм) |

Дексаметазон и миРНК против РКПГ |

PGE2 и редокс-чувствительный ПЭГ-модифицированный, поперечно-сшитый Te полиэтиленимин |

Крыса, однократно в/в на 10 мин реперфузии |

Ишемия 30 мин + реперфузия |

↑ захват кардиомиоцитами; ↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ апоптоза; ↓ фиброза; ↑ ФУ и ФВ ЛЖ; ↓ мРНК РКПГ; ↓ экспрессии РКПГ и ФНО-α |

[36] |

|

Полилактид-гликолид (148 нм) |

Дексаметазон и миРНК против VCAM-1 |

RGD пептид и редокс-чувствительный ПЭГ-модифицированный, поперечно-сшитый Te полиэтиленимин |

Крыса, однократно в/в на 10 мин реперфузии |

Ишемия 30 мин + реперфузия |

Накопление в зоне ИРП; ↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ инфильтрации нейтрофилами; ↓ апоптоза; ↓ фиброза; ↑ ФУ и ФВ ЛЖ; ↓ мРНК VCAM-1; ↓ экспрессии VCAM-1 и ФНО-α |

[37] |

|

Липосомы |

Резолвин D1 |

P-селектин мембраны тромбоцитов и редокс чувствительная |

Мышь, однократно в/в одновременно с реперфузией |

Ишемия 60 мин + реперфузия |

Накопление в зоне ИРП; связывание НЧ с моноцитами и макрофагами; ↑ эффероцитоза; ↑ ангиогенеза; ↓ размера рубца; ↑ ФВ и ФУ ЛЖ; ↓ КСО и КДО ЛЖ |

[38] |

|

Полилактид-гликолид, покрытый мембранами нейтрофилов и эндотелиоцитов (50 нм) |

Рофлумиласт |

Белки мембраны нейтрофилов и эндотелиоцитов |

Мышь, однократно в/в одновременно с реперфузией |

Ишемия 45 мин + реперфузия |

Накопление в зоне ИРП; ↓ размера инфаркта; ↓ инфильтрации нейтрофилами; ↑ ФВ и ФУ ЛЖ; ↓ экспрессии VCAM-1 и ICAM-1 |

[39] |

Сокращения: АФК — активные формы кислорода, ИЛ — интерлейкин, ИРП — ишемически-реперфузионное повреждение, КСО — конечный систолический объем, КДО — конечный диастолический объем, КФК-МВ — МВ фракция креатинфосфокиназы, ЛДГ — лактатдегидрогеназа, ЛЖ — левый желудочек, миРНК — малая интерферирующая РНК, НЧ — наночастица, ПЭГ — полиэтиленгликоль, РКПГ — рецептор конечных продуктов гликирования, TнТ — тропонин Т, ФВ — фракция выброса, ФНО-α — фактор некроза опухолей-α, ФУ — фракция укорочения, NT-proBNP — N-концевой промозговой натрийуретический пептид, TGFβ — трансформирующий фактор роста β, VCAM-1 — сосудистая клеточная адгезионная молекула-1.

Заключение

Стерильное воспаление представляет собой важнейший этап течения ИМ. Попытки воздействия на процесс воспаления при ИРП миокарда с помощью системного назначения иммуносупрессантов широкого спектра действия не привели к появлению одобренных для клинического применения препаратов. Это связано с наличием множественных дозозависимых эффектов большинства медиаторов воспаления, а также сложным пространственно-временным распределением процессов воспаления и репарации, специфичным для каждого пациента. Успешное клиническое применение многих препаратов ограничивается их низкой биодоступностью, недостаточной стабильностью и наличием серьезных побочных эффектов. Использование таргетной доставки противовоспалительных агентов позволяет приблизиться к решению этих проблем. Экспериментальные исследования последних лет показывают, что пассивная и активная направленная доставка препаратов, подавляющих воспаление, сопровождается их избирательным накоплением в зоне повреждения и усилением терапевтической эффективности. Перспективы совершенствования систем направленной доставки связаны с активным таргетированием поврежденной ткани, в т.ч. путем использования биоподобных покрытий лекарственных наночастиц на основе мембран тромбоцитов, лейкоцитов и эндотелиоцитов.